A nurse. With a sort of face. “Alicia, can you hear me?”

I nodded.

“Do you know where you are?”

“On the roof.”

“No, ma'am. You're in the hospital. You’re real sick, but you're gettin better. I'm proud of you, honey. We're proud of you.”

“I'm deaf,” I said, pointing at one ear, “from the cigar. Whose are these?” I said, lifting the box of cigars and relaxing into a folding chair, the Empire State Building to the rear of me, red, white, and blue.

Ahead was the Hudson River. It would be dark soon, and fireworks would split the skies between Manhattan and NJ, courtesy of the Macy's-sponsored flotilla.

“Whose cigars?” I repeated, louder.

They'd spread tar on the roof; you could walk on it, but the smell was infernal. The chair's legs were hollow metal, its fabric a woven, striped polyester. It and eight like it encircled a kiddie pool where bare legs stretched and feet splashed in its few inches of hose-water.

BAM BAM BA-BAM. BA-BAM BAM BA-BAM.

“—don't wanna be sedated,” a voice said. “We need your mind to be clear.”

“Who are you?” I asked it.

“Melody. Your nurse.”

“What happened to your nose?”

She seemed startled. Felt of her nose. “Why, nothing.”

I hated to be the bearer of bad news. But that box of cigars, turned out they were exploding ones from Ira’s Gags and Novelties over on 10th Avenue.

Melody didn't know that, and she'd decided to smoke one. It wasn't a bam, it was a sharp CRACK and then smoldering confetti.

I jumped up in a frenzy. The folding chair flipped. Palming my ears, I ran in tight circles. “I can't hear!”

“You heard fine earlier,” Melody said.

Now I was deaf because some stupid out-of-work actor — “The box said exploding! What the hell, Ali?” he said.

I grabbed Melody's hand. “Four years in Hell's Kitchen. There’s gotta be a Plan B. My novel stinks, Melody. It stinks.”

“You wrote a novel? How great is that?”

“Why won't it end?”

“Why won't what end, honey?”

“My novel! It keeps going on and on, it won't end, and these shitty freelance jobs. I'm twenty-six! You know how old that is, authorially speaking? Thirty you're dead.”

“You’re not dead. You're fightin to live.”

“LOOK.” I twiddled my fingers. Beneath the sheets, I bounced my toes. “I can’t control my fingers. I can’t control my toes. Just put me in a wheelchair.”

“You need the bathroom?”

“I'm going to graduate school. I can't do this anymore.”

“Do what, honey?”

“This city. The freelance jobs. Being broke. Getting mugged.”

“You were mugged? When? Recent?”

“You try having five guns pointed two inches from your face. I didn't fight. I just gave them her ring. I gave them Grandmother’s ring. I shouldn't have done that.”

“You did what you had to do to stay alive.”

“Alive? This isn't life, it's a lifestyle. I want a life, a real one. I can't go on like this.”

Vladimir: That's what you think.

I side-eyed Melody.

“You're an Absurdist nurse?”

“Alicia, we need you to focus, stay present. Can you do that?” She snapped her fingers.

“I'm dying,” I said. “My stomach is killing me.”

“Blood pressure's way low,” somebody said.

When I woke in the night, I was horrified to learn that Melody had been killed by a coat rack. It was standing between me and the window, facing me, but faceless, because it was wearing an astronaut’s helmet.

I felt around for the buzzer. Pressed it. After a few seconds, the coat rack said, “How ya doin, Alicia?”

“May I speak with a human, please?”

“You're good,” the coat rack said. “I'm Kevin. What's up? What do you need?”

“Where's Melody?”

“Her shift ended. You're okay. We can see you through the camera. What do you need?”

I scanned the walls and ceiling, trying to orient myself.

“Behind the robot's visor,” Kevin said. “It's a security and communication device. I'm at the Nurse's Station. You're good.”

“What year is this?” I asked. My voice sounded distant and small.

“What year do you think it is?” the robot asked.

“2001?”

“You think it's 2001?” From his tone, I concluded it wasn't.

“1979?”

“Okaaay, listen, I'll be in to see you shortly, Alicia, is there anything else you need?”

“Why do you and Melody sound southern?”

“It's how we do it in Nashville.”

“The nurse's station is in Tennessee?”

“You are, too, Alicia.”

“I'm in New York.”

“Not anymore.”

Somehow I'd traveled to the future. Worse yet, Tennessee. All that travelling had worn me out until my mind wasn't my own anymore. It started and stopped, then stood there waiting, as if what I'd forgotten might show up.

“What’s happening to me?” I asked the droid.

“What kind of tree is the Scholar Gipsy sitting under, and why is that significant,” he asked.

“Yew tree,” I said. “Symbol of death and—”

“I'm the real thing, Alicia.”

“Death's a droid that looks like an astronaut’s coat rack?”

“The better to hang your old tattered coat on,” he said.

Now I understood! I wasn't in the hospital—I was taking an exam! Putting an index finger in the air, I wielded it like a pen. The pen wrote itself into a boat sailing

to Byzantium.

“Good news, Alicia,” a woman’s voice said, “your fever’s down a bit.”

“Melanie!”

“Mella-dee,” she said.

“I thought Kevin killed you. He's Death Itself.”

“Alicia, I want you to stop with all the death talk. You have sepsis, and it can do a number on the brain. You’ve got some delirium, but you're full of antibiotics. You’ll get your bearings back.”

“What bearings?”

“Kevin said you were still unsure of time and place. Do you know where we are and what year it is?”

“Grad school.”

“No, honey. You're in the hospital. I think graduate school was a looong time ago. You're almost seventeen now.”

“At seventeen, I was in high school.”

“Seventee,” she said.

I got a kick out of that. “What’d I do with my life? I didn’t waste it too much, did I?”

“You don't remember anything after grad school? At all?”

I glanced at the bedside table. “Where's a mirror?”

“Unh-unh, wait,” Melody said. “I'm gonna see if the doctor wants to order more tests first. Will you just sit tight? Can you do that for me? Don't look at yourself til I get back.”

“Why not?”

“How old were you in grad school?”

“Late 20s, early 30s.”

“Don't look til I get back,” she said.

I looked.

I'd turned into THIS.

My hands. I felt of my boobs, my neck, my jaw. They sagged! They weren’t mine. My hair was all dried-out, it used to be soft, what the hell kind of boring hairstyle? My waist. I had no waist!

“I want my waist back!” I shouted.

Now I understood—I was in a horror film taking place in an evil hospital. They were harvesting youthful bodies to sell on the black market, then stuck donors like me with old used ones.

“Kevin,” I said, “they snatched my body!” He was Kevin McCarthy, star of the original “Invasion of the Body Snatchers.”

Tearing the blanket from my feet, I gazed at them. Bunions! And they’d removed my ankles and attached my calves to my feet. Cankles! My strappy blue suede 5-inch platform sandals. I'd paid a fortune for those sandals, and now I couldn't wear them. If only I hadn't fought so hard to live.

“All those memories lost in time,” he said.

Like . . . tears in rain? That wasn't Kevin McCarthy.

“I want you to know I have great sympathy for replicants,” I said. “Is Roy Batty your friend? He's a Byronic hero. He’s not a villain. Tyrell is. And Decker. How much longer do you have to live?”

“That's very good, Alicia,” Kevin said. “For a woman who had her memories stolen, you’ve held on to what matters. 3.8763 years,” he said.

Oh, poor Kevin.

“Do they at least pay you well?” I asked. “Can you afford safe housing and healthcare?”

Melody was back.

“We need to see Dr. Tyrell,” I told her.

“Honey, I don’t know a Dr. Tyrell.”

“He only gave Kevin 2.9763 more years to live, and I want to know why. Roy was right. What kind of a monster creates life only to destroy it in its prime? Or steals our youthful parts and replaces them with sagging crap like this? I demand an audience with Dr. Tyrell.”

Her face melted, then turned into an intercom. I was Sigourney Weaver, and she was that awful computer, Mother.

“You bitch!” I said, picking up the flame thrower.

“Alicia, if you can't calm down, we'll have to bring in a psychiatrist. Have you ever been told you’re schizophrenic? Bipolar?”

“Tyrell gave me Alzheimers.”

“Has a doctor told you that you have Alzheimers or dementia? There's no mention of that in your records.”

I began to cry. Alicia bent to pat my shoulder.

“You’ll come out of it,” she said. “You just need to relax. Are you hungry? Would you like some scrambled eggs?”

“Oooh, no, my stomach is killing me. I have scrambled brains. Inside me, where we store memories and experiences, there's nothing now. It's like I never lived. I just got old.”

“I took them,” Kevin said.

“Took what?”

“Your memories.”

“Why?”

“I like them.”

That bastard.

“How dare you violate me like that! Those memories are mine. They're private. You had no right. You've done a terrible thing, Kevin. Melody, I want to press charges,” I said, but she wasn’t there any more.

“Alicia, you heard what that nurse said. You need to relax.”

“Fuck you, Kevin, and get out of my room. Women aren't safe around men like you. You’re not the first rotten apple I've dealt with.”

“You can't know that without your memories.”

“I can feel it, Mr. Smart Guy. Humans possess a superpower your kind never will. We know things in our cells and marrow and gut, not just our memories.” Rolling to my side, I turned my back on him.

“Angry women are unattractive,” he said.

“Oh, shut up, I'm free from all that crap now that I'm older than God.”

“Suggest a solution to your anger,” he said.

“Give me back what's mine.”

“That's not how the algorithm works.”

“How does it work?”

“Give me a prompt.”

“Okay, who were my parents?”

“Your father abandoned your mother when you were two.”

“My poor mother!”

“Would you like to see a picture of you and your mother?”

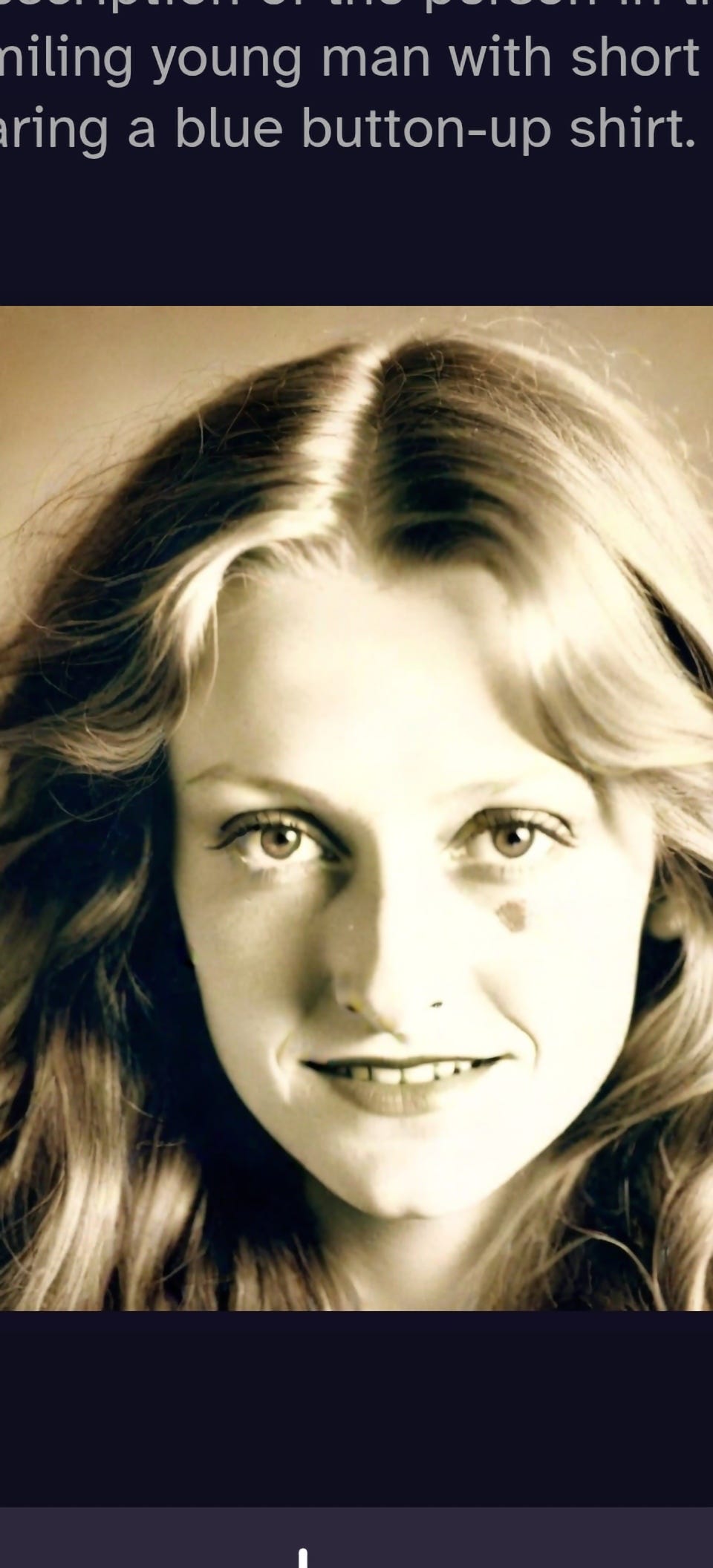

“Yes!” Rolling to face him, I watched this flash onto his visor:

“I was abused?”

“It wasn't perceived as abuse then, Alicia. You liked school. Would you like to see a picture of yourself at school?”

“Sure!”

“What were we hiding from?”

“Nukes.”

“Oh,” I said. “I remember now. Russians. That's really me as a child?”

“It's a stock photo.”

“You said I'd get to see a picture of me.”

“I apologize for the misunderstanding. I can show you a picture of you if you'd like.”

“I'd love that.”

“Why is that child wearing lipstick and mascara? That's so creepy.”

Her eyes felt like mine. The hair color seemed right. The braids felt right. But — “Kevin, I feel like I had freckles across my nose. And my teeth wouldn't have been that straight yet, or dayglo white.”

This popped onto his visor:

“What the hell is that?” I said.

“You wanted a freckle.”

“No, what's that text on top about a young man in a blue button-up shirt? Was he someone important in my life?”

“Just one more failed actor.”

“What was his name?”

“Does the name John feel right?”

“I guess.”

“His name was John.”

“Do you have his picture?”

“He became a clown?”

“Among other things.”

“I don't like what you're showing me.”

“I gave you the freckle you wanted. Your teeth aren't as bright. Would you like me to suggest ways you can be more appreciative, Alicia?”

“She has my eyes and hair. But those aren't my teeth, I don't have a dimple in my chin, and I don't have a birthmark under my eye. It's just off, Kevin. It's not real, and I resent your attempts at manipulating my reality.”

“Is this more to your liking?”

An ad for hair and makeup?

“My eyes are blue, Kevin.”

“Oh, my God! What is that?”

“You look lovely,” he said.

“Kevin, my brain may be scrambled, but one thing I do know is that I'm not a robot.”

“Yet.”

“What did you say?”

“Are you pleased now that you have a better sense of your life, Alicia?”

“You just showed me manipulated photos of my young face and some clown. I don't ever age in them. The plot of my life . . . just sweats in the dark like . . . a face.”

“Would you consider your wedding part of the plot?”

“I was married? Well, sure, of course.”

“Oh, Kevin, that's just the same old photo you've been doctoring. Now you've made me a bride. Where’s the groom? I want to see the man I married.”

“Certainly.”

“Oh, my God, those eyes! He is familiar. What possessed me to marry a man with eyes like that? Oh, turn him off. I don't want to see him anymore, Kevin!”

“Will it please you to know you divorced him?”

“Thank God because I think he was abusive — his face gives me such a negative visceral response. Please tell me I didn't have his children.”

“You never had children.”

“Thank God.”

“With fingerprints,” he said.

“What's that?”

“You were one of my teachers. You trained me in the American novel. Don't you remember?”

“I can’t, you took my memories.”

“Does the photo feel right to you?” he asked.

“What novels did we study?”

“Long ones.”

“Did you like the class?”

“I gave you a poor evaluation.”

“Why?”

“We wasted three weeks discussing Moby Dick. I only needed 27 seconds to read it. Do you think you could have talked more, Alicia? Wasted more of my brief life?”

“Oh, no, I was a bad teacher. I failed you. And now I'm old and feel clammy. It’s hard to breathe, and my stomach hurts so bad. Worse than anything I’ve ever felt. Am I dying, Kevin?”

“You're going through a challenging time. Would you like me to suggest a way for you to not die?”

“You have the power to keep me alive?”

“I do.”

“That would make you God.”

“Do you think I'm God?” he asked.

“I don't know what I think. I just don't want to die not knowing who I was. I don't know who I was, Kevin. Tell me.”

“What is that?” I said. “Wait, I know that bike. They called them klunkers. It does seem familiar.”

“How about this?” he said.

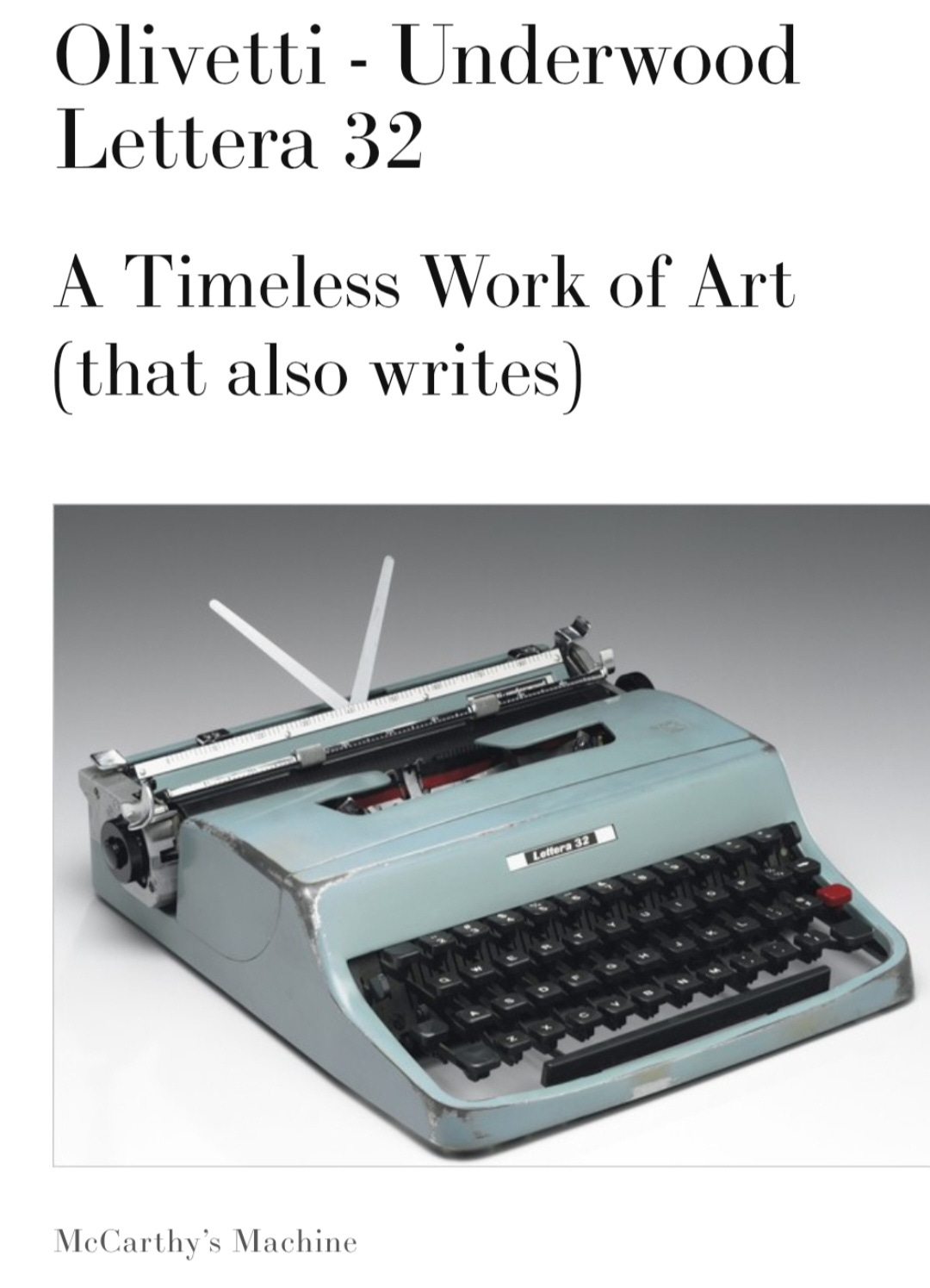

“Yes. I knew Lettera.”

“She was my grandmother,” he said. “You started a novel with her but never finished. You created a character in that novel — the bike. But you never finished the bike's story. Do you know what a betrayal that is, Alicia?”

“I guess I thought it wasn't very good.”

“Did you ever give a thought to what my grandmother thought when you just gave her away and left New York City? What Speedy Feet thought when you tore up the plot of her life?”

“Who's Speedy Feet?”

“The protagonist. The klunker.”

That didn't feel right. “Wasn't there a girl riding that bike? And . . . a dog she rescued. And . . . two dangerous men? Descended from the Harpe Brothers. Yes! And . . . there were other bad men and they were . . . chasing her — it was a story about people, Kevin, and the mountains, the land they lived on, and how the land should be used best. And — they murdered her father! That poor girl,” I said.

“Why would you feel sorry for her?” he said. “She wouldn't want your pity.”

“Oh, my God, Kevin, you're disgusting.”

“Why? You remembered her, so there she is.”

“What's that thing between her legs?”

“The seat.”

“No, it isn't. She's 15-years-old. Back off.”

“Do you want to live, Alicia?”

“I saw my face, I know I'm old enough to die, but in my mind, I still feel young.”

“That's the delirium. Your mind is old, too.”

“This is Hell's Kitchen,” I said, “and you're the devil.”

“I'm going to read you the only passage that's worth anything from your novel,” he said. “And then you're going to tell me the ending that you never wrote. Not the ending of the girl or the dog or the men or the mountains. I want to know what happened to the bike.”

“Why don't you write the ending? If you can read Moby Dick in 27 seconds, this ought to be a breeze.”

“Do you want to live or not, Alicia?”

“Are you saying you'll kill me if I don't tell you the ending? I never finished so I don't know what happened to the bike.”

“All I have to do is unplug that IV.”

“An alarm will go off, Kevin.”

“I'm the alarm.”

When I awoke, I could smell the evil. It was Dr. Tyrell asking Melody if I was a DNR. “Yeah,” she said.

“Ventilate her.”

I decided to fight him, only when I tried throwing a right hook, my wrist stayed tied to the headboard. My hands were in boxing gloves.

“Kevin,” I said. “Was I a boxer in college?”

“Archery,” he said.

“How come they gave me boxing gloves? Are they laying bets on me?”

“You became physically aggressive, Alicia.”

“Me?”

They began forcing something machine-like onto my face. I boxed and boxed and boxed and boxed, but the gloves only bounced up and down.

“Kevin,” I said, “am I like you now?”

“You're a beautiful young borg,” he said. “Are you ready for a bedtime story?”

“Okay.”

But it didn't make sense: My bike was beautiful but not sleek because that was of no advantage in the mountains. What she had to be was a thick and quilted thing, a hybrid sewn by my father of carefully chosen parts from traditional bikes that, added up, formed something new and so extraordinary she navigated terrain the others couldn't. She sported balloon tires, fire engine red fenders, a mahogany leather seat and silver torso. I loved her, kept her well-tended. She was my connection to my father, and a boon companion. I would return for her if I had to die trying.

“What happened to the bike?” Kevin said.

“You lied. You said my father abandoned us when I was two. He died of cancer when I was twenty.”

“I spoke in error.”

“You're full of shit, aren't you, Kevin? Let’s redefine my death, why don't we? The actor you called John. What was his real name? What happened to him?”

“It's a sad story. And you're not well.”

“Cut the crap.”

“He got an MBA. Became a hedge fund manager. Still married to his first wife. Owns a big place in Connecticut.”

“I doubt he's too sad.”

“Remember when you left?”

“From Penn Station.”

“He tipped his hat.”

He did, and he kept it lifted until he and the platform drifted away.

“I think I also loved the man I married. He wasn't psychotic or abusive, was he, Kevin?”

“Humans like saying they have a crazy ex. I thought it would make you happy if I validated that.”

“Well, it doesn't. He never lifted a hand against me. We danced barefoot . . . a lot.”

“You divorced. How good could it have been?”

“Love’s not black and white,” I said. “Grow up.”

“What happened to the bike?”

“I think I loved teaching, too. I remember writing on a white board. With a . . . green marker. EMILY DICKINSON. And all of a sudden . . . I came out of my body, I could see me talking, I could see my students . . . they were listening and taking notes. And it hit me. Look how I happy I am. And coming back into my body . . . and saying to my students, ‘I want to thank you for being here. It's an honor to be your teacher. I can't believe I get paid to do this. Oh, wait,’ I said, ‘I guess they don't pay me,’ and my students laughed. They got the joke. Oh, Kevin,” I said, tugging my arms against the restraints, “it was an honor. I was blessed.”

“What about the bike?”

“There was a dog. A lot of dogs. I did that, Kevin. I rescued dogs.”

“I'm only going to say it one more time, Alicia. What happened to the bike.”

“There was a cabin I restored. In the mountains. I made a beautiful garden. People would drive by, and they'd back up just to look. They'd take pictures. I waved from the porch.”

“I'll count to three. One.”

“I remember, Kevin.”

“Two.”

“I was blessed,” I said.

“Should I unplug her?” the bike asked.

“Yeah,” Kevin said.

This is brilliant! You sucked me in so fast to the world, and afterwards I was reminded of the speech pattern of HAL from 2001: A Space Oddysey, and reminded of WALL-E feeling sad for all that he and Earth had lost, and K-9 from Doctor Who. And a character I wrote who was at end of life and nobody was listening to him ( must dig that out!).

So cleverly done. Love it 😊

This was absolutely excellent! The references to Blade Runner are so well placed. The pace and style of the dialogue are very reminiscent of the scenes were they are testing people to see if they are "Replicants". Outstanding! I hope you'll give us more sometime.